Discover more from DARK FUTURA

Have you ever noticed a group of people belonging to a certain taxonomy which lives life in a strangely oblivious manner, as if disconnected from the rooted instincts which hold many of us together? This class of people roaming the world I have dubbed the dissipative people. They seem to go against the grain of natural currents, living in the sway of habits which are over time destructive.

Granted, many of you reading this could be among them, and there’s nothing wrong with that. After all, I believe it’s a sort of hereditary curse, and many just can’t help themselves. But as someone who’s always felt acutely tuned into life’s minute rhythms, with a heightened sensitivity for the bodily circadian flows and natural phases on which we drift through this world, it’s striking to watch people who lack such awareness bumble through life, often doing grave harm to their health by virtue of disconnect from their body-environment symbiosis.

What is this dissipation, exactly? It’s a neglectful marshaling of one’s thoughts and the natural biorhythms of life. The common trait found amongst this clade is a wasteful inability to find restful sleeping habits for their body. They often find themselves strung out on their couches, absently staring into the mindless glow of the TV until 5 or 6am, only to pass out in some uncomfortable splay in a cheap imitation of sleep.

They’ll wake after only several hours, groggy-eyed and dazed, ignoring every bodily signal of alarm or distress, only to push against the current of their body’s natural defenses. A similar attitude exists towards eating and nutrition—the reflexive mechanisms which normally alert us to such basic things as not overeating past satiation are out of whack. This includes things like eating at odd hours, particularly types of foods that are incongruous with the phase of the day, like heavy, greasy foods before sleep. They then wonder why they have chronic heartburn and other ills.

These people usually lack a structured inward sense for time and planning. Husbanding their internal energies, particularly the psychic energies of ego depletion comes as a great burden for them. They may have an important meeting in the afternoon, yet they’ll spend the morning howling and raving at something, profligately unspooling themselves, only to feel drained and ‘inexplicably’ confused by the time of the meeting. Their sense of scale and balance is off, leaving parts of their day overladen rather than an even distribution of exertions.

They are a people removed from a certain naturalistic rationale; for instance, someone who knows that hard rain is coming, but simply refuses to shut the windows, electing instead to ‘clean up the mess later’, despite it taking far more effort to mop up the drenched floor and soiled furnishings than it would have taken to close the window at the outset. It’s a manner of backward living which can easily be dismissed as simple laziness, though there’s more to it than that; it’s akin to a sluggish up-river plod against life’s invisible current.

This isn’t new-age gospel or one of those moralizing pseudo-yogi ‘tips for better living’. And this isn’t to preach some strict commandments of a ‘healthy lifestyle’, giving up seed oils, enrolling in an arbitrary regimen of quasi-religious fasting and other cheap pastiches of ‘ancient wisdom’ regurgitated for a wayward, spiritless, and spiritually-bereft modern audience. I don’t claim to follow any specific belief or be a practitioner of any arbitrary set of rules or guidelines. This is all just a set of natural observations accumulated over a lifetime by way of a sensitivity to life’s hidden murmurs. There are many out there who are in tune with that sense of greater consciousness and conscientiousness; people with a developed sense for natural stillness, a sort of holistic and naturopathic sensibility which exists outside of prescriptive guidebooks.

As mentioned, part of it consists of being naturally observant: of one’s environment, of others, of one’s own body. It partly stems from an ingrained introversion, as loud, socially active people often deprive their daily experience of the isolation necessary to be truly intune with their body’s subtle responses, that endless negotiation of flesh and environment.

Many of us have known people—typically women—who are highly attuned to their bodies, particularly with regard to menstrual cycles and hormonal phases. They can isolate the slightest inward disturbance with the sensitivity of a migrating pigeon’s magnetoreception. Some of you might be one of those people yourselves. At times they can be either puzzling or irritating, being servants to the mysterious ebbs and flows of their internal world, and often letting everyone know about it with the wide-eyed persistence of a proud Vegan.

Science is replete with examples of people with abnormally acute sensitivities. There’s a woman who can smell cancer and Parkinsons on people, for instance:

A whole class of blind people exists, which can navigate the world by echolocation with such acuity as to even ride their bikes through busy streets, and detect the presence of cars and obstacles on the fly.

Dissipative people occupy the opposite end of this spectrum. They’re blind, deaf, and dumb to their body’s warnings; eating at odd times, overindulging repeatedly to the point of nausea, then wondering in total obliviousness why they’re always feeling so off. They have lost their sense for life’s golden mean, which endows a logical awareness for things like moderation and forethought.

Of course, to understand moderation is not a super power. Most people have at least a serviceable sense for it, if not a keen one. The point is not to glamorize the ‘highly sensitive’ as some kind of enlightened gurus or mystics, but rather to explore the puzzling mystery behind how some people’s mind-body connection can be so hopelessly frayed, and what that means for humanity at large.

In today’s Bronze-Age-Revivalist craze du jour, we’re inundated with talk of reformulating ourselves, in a holistic sense, as strong and enlightened citizens in the stripe of the philosopher-king ideals held to such esteem in ancient times. We hear of things like the Greek Paideia as a rubric for creating the model citizen, or raising the perfectly well-adapted patrician scions. It’s an idea that privileges both mind and body training to create a harmoniously balanced and elevated individual.

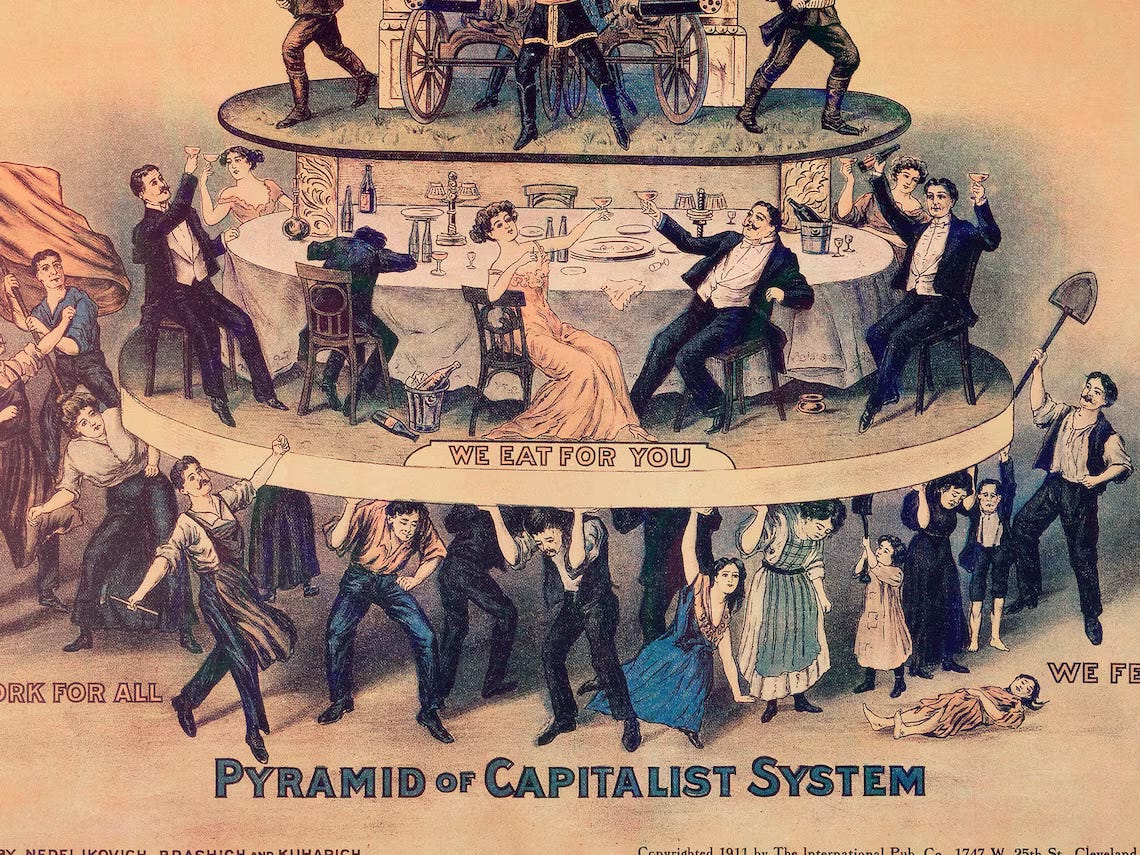

It’s but one thread of many in today’s discourse, as society’s underclasses attempt to wrangle the problem of what the post-Davos future should look like, provided we get past the current tipping point before the meta-narrative of the Old Europe banking class wraps us in its coils. What does a truly free society look like in the post-Western-Banking-Cartel world? What does the individual, the autochthon of such a world resemble?

Many of modernity’s trappings have removed us from any semblance of a connection to the natural world. I don’t mean that in the hippie sense of stomping through wildflower fields, barefooted ‘grounding’ to the soil. Certainly that can be part of it, if you’d like. But what I’m referring to is more in the metaphysical sense of our relationship to the reality around us.

Modern living consists of a continuous stream of narratives vying for the finite shelf-space of our minds. We’re pulled in all directions by forces with their own individual motivations. These motivations typically require them to reconfigure our reality constructs, and the way we process our realities, in order to heighten our receptibility to the power of their intention. We’re left in a boggled state—as mere empty vessels, each day drained and refilled ad nauseam by malign matrices which are inherently out of sync with the natural order.

It gets to the point that we ‘forget’ how to process authentic sense-information filtering into our own bodies from the environment around us. I re-iterate, this isn’t a prescriptive pamphlet on paleo-living or an advocacy for some Bronze-Age-adaptivist, neo-reactionary, technoprimitivist, or archeofuturist lifestyle. Though incidentally, it does jibe with Guillaume Faye’s ideas in his seminal Archeofuturism, some of which are interesting. In particular, his term ‘ancestral values’ to represent what we should be striving for is one that makes sense. Likewise, he aptly named the next period which awaits us as the ‘post-catastrophic age’ or ‘post-catastrophic world’. He identified the current devolution of society as an age dwindling intransigently into ‘catastrophe’, caused by centuries of Enlightenment-inspired ideologies, like those of humanism, egalitarianism, individualism, and most perniciously—liberalism.

It turns out that we all intuit that the world is at a critical juncture. A point in history that faces both backward and forward. We can feel that there’s something off about the modern era, not in the overt spectacle of the poisonous cultural movements, but at the most fundamental level: how ordinary people live each day, the types of relationships we have with our surroundings, environment, our own bodies. There’s been a sort of decoherence, a loss of proportionality—the inward, intuitive understanding of those golden means of daily existence.

The modern existence is a cobble of shuffling souls, stumbling through life as their essence seeps out of them, slowly dissolving into the great gelatinous mar. Rather than being coordinated and working in concert efficiently, their energies are diffused. And like a leaky tanker, inordinate expenditure goes toward just patching up the outflows, which drains them and creates a self-eating cycle. Ego-depleted, the rest of their time is spent in a sort of convalescent stupor, always ‘several steps behind’ the ebb and flows of existence.

One of the agreed-upon primary issues with modernity has always been the lack of purpose. We live not only in an age that has shunted aside the various metanarratives of the previous eras, which—fictive as they may have been—gave people purpose, reason, and structure, but also an age that has foresworn beauty and complexity, in things like art and architecture, to be replaced with barren, unimaginative design.

To live amid such uninspiring surroundings takes something unspoken and perhaps essential from us. It fills us with the nihilism necessary to hang our heads and report for duty to our drab 9-to-5s, as if by design. Beauty endowed with symbolism makes us feel a part of something larger, fills us with the ‘holy spirit’ of wonder, which subconsciously trickles down into our daily deeds, leavening them with tinges of subconscious meaning. This consequently has a cascading effect on everything from our zeal for life itself, to our hidden desire to be in sync with something much larger than ourselves, the universe’s grand design.

But the trappings of our modern milieus instead leave us feeling bereft and isolated. It’s therefore no surprise that society is filled with the wayward souls, those dissipative people, who trudge upstream while their life spools out of them like effluent into a drain. To counteract this, modern movements have sought to over-compensate for the drudgery and dissolution by idealistically attaching themselves to some other foregone culture. Let’s live by the code of the Greeks, or the Egyptians, the inhabitants of the world of Homer’s Odyssey or Bhagavad Gita or some even more remotely obscure fixation—a gnostic desert tribe, perhaps.

All of these societies were fraught with the same ills and perils as our own. Cherry-picking the odd exemplary pearl from one century or another is akin to using confirmation bias on one’s preconceived notions. The appeal is obvious: it provides us with a sense of purpose to believe in the superiority and enlightenment of some previous culture from long ago, creating something to strive for; an end goal. It also provides a convenient—albeit disingenuous—juxtaposition to modern life, which allows us to more easily critique modernity.

But when you compare the cherry-picked highs of one civilization to the diametric lows of another, you’ll always present the appearance of a great divide. It will seem like centuries or even millennia had swallowed whole humanity’s progress, left us quivering at the frayed edge of the kali yuga with something essential missing, gone forever. But what is hidden is not lost; the same fundamental instincts deep inside, which were the coal beds alight with the ethics and moralities hallmarking previous eras, still lie inside us to be uncovered and dusted off.

Natural principles inhere in all of us, though often drowned out by modernity’s noisy grasping. To sew up the seams of dissipation, we must align with our chosen purpose. This isn’t of the rarefied ‘cosmic’ variety—though if that works for you, by all means. But simply the purpose of directed intention for our lives from the pragmatic standpoint, and both micro and macroscopic perspectives. Purpose simply implies a concentration of the will, an active and intentioned narrowing of our thought processes. It’s the direct antipode to dissipation, which implies diffusion, a dissolving of your will into that grand homogeneity of modernity, the ultimate pull of some wimpled egregore toward total bio-uniformity.

Many ancient cultures practiced such concepts. Though it may seem contradictory to my earlier point against ancient guides—I meant that in the sense of blind obedience to and idolization of the old simply for the sake of its antiquity. But we can certainly still use them as frameworks and examples towards understanding. For instance, the Egyptian Ma’at consisted of a set of internal moral and ethical principles to live by. Akin to the notion that truth is immanent in us by nature, removed from exogenous sources. Ma’at was applied to law as well, likewise offering an internally derived application of justice, rather than one relying on rigidly preordained laws.

From the wiki linked above:

Maat was the spirit in which justice was applied rather than the detailed legalistic exposition of rules. Maat represented the normal and basic values that formed the backdrop for the application of justice that had to be carried out in the spirit of truth and fairness. From the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2510–2370 BCE) onwards, the vizier responsible for justice was called the Priest of Maat and in later periods judges wore images of Maat.

In some ways, such principles can be compared to the later Chivalry in the West or Bushido and Tao in the East.

Tree of Woe recently discussed it, citing a paper which fascinatingly described how ancient Egyptians believed that Ma’at was the chief force in holding back the void of ‘Chaos’ in their daily lives, and the world itself:

In Ancient Egypt there was an obsession with holding back chaos ỉsft through following your maat, your duty is to follow your maat to help hold back ỉsft. Every person at every level of society had their own rules to follow based upon their station in life, and to not follow them ran the risk of chaos breaking forth and destroying the cosmos. For the ancient Egyptians chaos was society fallen and much of pharaonic ritual was believed to play an important role in keeping it at bay. Here chaos and monarchy are diametrically opposed to each other in a cosmological battle for all eternity.

Such an interpretation appears quite relevant to our present day. Living life in a dissipative manner, without the lodestar of intentionality and conscientiousness, does slowly welcome the seep of Chaos through the sieve of our neglect, which thereby threatens to overrun society when enough have fallen victim to its absent-minded paralysis.

That’s because the more we sleepwalk through life in this manner, the more we yield control to those above, the will-vampires and debt archons who work daily toward turning us into passive, obedient chattel for the purposes of maintaining their own centuries-old status quo, and perhaps even darker, esoteric things.

Only true intentionality can help turn back the tide. Another author recently broached the topic from a theological and Thomistic perspective. He talks about mindfulness and temperance, aptly writing:

The West sometimes conflates Mindfulness with “living in the moment.” Mindfulness is more precisely active awareness of the present. Active awareness involves interpretations of sensory data based on past experiences and the potential impact any present action may have on the future. To live entirely in the present is to lead a less-than-animal existence. Even a flatworm can learn to avoid electrical shocks.

And that is the ultimate point: absent living leads to the void of Chaos, that tabula rasa imposed by the Lenders to crack open our postern gates just enough for the slow seep of their own reality to welter us in its narcotic daze, reconfiguring us to their purpose. Chaos is the Global Homogeneity which presses in, easing through the gaps of our oblivious neglect, one miasmic step at a time, whenever we let our guard down to drift into a dissipative fog. Each considered choice we make, each refrain from the daily mental lapse of ‘animal living’ is a thwarting blow, a cagey lash at the silhouetted beast, limned in lightning, growling at our den’s entrance.

Let us own our thoughts, and together, hold back the void of Chaos.

If you enjoyed the read, I would greatly appreciate if you subscribed to a monthly/yearly pledge to support my work, so that I may continue providing you with detailed, incisive reports like this one.

Alternatively, you can tip here: Tip Jar

Not to be a contrarian, but working in oncology, often one meets people who "did everything right." Meaning, they eat right, exercised and meditated, went through annual screenings, etc., and when diagnosed with cancer, they are they are absolutely stunned. It's like they thought by doing everything right, they made some kind of pact with God to be spared. At least for someone who "deviated," they can revamp their lifestyle, change their outlook, but when you "did everything right," and ended up with cancer, the hard landing is much harder indeed....

Look up Iain McGilchrist. He's saying the same thing as you. He is a neuroscientist and philosopher who delves into how we attend to the world. One manner of attending is to focus, to find food and shelter. But that can't be the only way of attending. The other way must attend to the whole environment, to be aware of danger from predators, or the need to attend to offspring. It is this fundamental need for these two types of attention that give rise to the two hemispheres of the brain, that are found in all animals.

The left brain attends in a focussed way, to be able to grasp, manipulate, and control. It freezes things, isolates them out of context, breaks things into parts, abstracts and generalizes. The right brain is grounded in reality, a changing, flowing world, where everything connects in some way to everything else. "Part of it consists of being naturally observant: of one's environment, of others, of one's own body." This is essentially the right brain's way of viewing the world.

McGilchrist contends that since the Enlightenment, the worldview of the West has become unbalanced, with the left brain taking over, and shutting out the right brain. It's not that we don't need or want the left brain's input, but that there needs to be a balance. I find that this view explains a lot. There is definitely something fundamentally wrong with the mentality of the modern world, of how moderns see things, how they process things.

I can't explain this all in a single comment. Here is a video interview of McGilchrist expaining it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TrlrhuI39K4.