I was wrapped in thought the other day, meditating on good writing and what distinguishes it from the merely average. I had read a new article by one of my favorite writers in the manner that I usually do—you see, us writers, or creatives in general, do not enjoy the luxury of merely reading for pleasure, as normal people of the quintessential ‘audience’ do. We must in fact approach reading with a scrutinizing eye, sometimes taking in the text in chunks to contemplate and process the aspect of craft which we’ve just imbibed.

Writing at a high level is not easy. To dance on the knife’s edge of both inspiration and mechanical facility does not merely come natural at all times. In art, one learns that there is no such thing as having reached an innate level of ultimate ‘mastery’ that grants you an irrevocable license to produce ‘greatness’ and ‘quality’ on command; it simply doesn’t work that way, unfortunately. Or perhaps, I should say fortunately, as it accords with the theme whose contours I’m now tracing.

As is the wont of any passionately aspiring writer, I’ve read my share of ‘how to’ books, which include all the popular ones like Stephen King’s On Writing, to more obscure ones like Robert Olen Butler’s From Where You Dream, which approaches the art from less a traditionally didactic and more an inspiration-centered and creative lens. One thing some of the better books teach is that good writing is very often unexpected and surprises the reader with novel takes on familiar and well-worn scenes or tired tropes, whether it’s from the thematic and storyline standpoint, to even the grammatical sentence level one.

Alice Laplante’s The Making of a Story, for instance, teaches how one must avoid cliche—that is, the expected response or resolution to a given setup. As example: if a character is on their deathbed, it’s best to dodge the most expectedly maudlin dialogue exchanges, the weepy goodbyes and sentimental pauses. It’s better to surprise the reader with something they hadn’t experienced before in that type of scene—something which could make the character’s death far more memorable, standing out amid the endless retreads.

She gives an example from Larry McMurtry’s Terms of Endearment:

“First of all, troops, you both need a haircut,” Emma said. “Don’t let your bangs get so long. You have beautiful eyes and very nice faces and I want people to see them. I don’t care how long it gets in back, just keep it out of your eyes, please.”

“That’s not important, that’s just a matter of opinion,” Tommy said. “Are you getting well?”

“No,” Emma said. “I have a million cancers. I can’t get well.”

“Oh, I don’t know what to do,” Teddy said.

“Well, both of you better make some friends,” Emma said. “I’m sorry about this, but I can’t help it. I can’t talk to you too much longer either, or I’ll get too upset. Fortunately we had ten or twelve years and we did a lot of talking, and that’s more than a lot of people get. Make some friends and be good to them. Don’t be afraid of girls, either.”

“We’re not afraid of girls,” Tommy said. “What makes you think that?”

“You might get to be later,” Emma said.

“I doubt it,” Tommy said, very tense.

When they came to hug her, Teddy fell apart and Tommy remained stiff.

“Tommy, be sweet,” Emma said. “Be sweet, please. Don’t keep pretending you dislike me. That’s silly.”

“I like you,” Tommy said, shrugging tightly.

“I know that, but for the last year or two you’ve been pretending you hate me,” Emma said. “I know I love you more than anybody in the world except your brother and sister, and I’m not going to be around long enough to change my mind about you. But you’re going to live a long time, and in a year or two when I’m not around to irritate you you’re going to change your mind and remember that I read you a lot of stories and made you a lot of milkshakes and allowed you to goof off a lot when I could have been forcing you to mow the lawn.”

Both boys looked away, shocked that their mother was saying these things.

“In other words, you’re going to remember that you love me,” Emma said. “I imagine you’ll wish you could tell me that you’ve changed your mind, but you won’t be able to, so I’m telling you now I already know you love me, just so you won’t be in doubt about that later. Okay?”

“Okay,” Tommy said quickly, a little gratefully.

LaPlante elaborates:

Talk about a situation rife with pitfalls of sentimentality! A dying mother on her deathbed, talking to her sons for the last time. Yet McMurtry avoids giving us any “expected” or overly familiar dialogue. He grounds us thoroughly in the world of the story, in the characters and their relationships, and we pull through this difficult moment relieved—and infinitely moved.

And her kicker:

How do we manage to write things that are neither melodramatic nor sentimental? Simple. By noticing things. Really noticing things. That is our first job.

She explains that, in essence, what makes us truly human is our ability to notice and act on the minute and seemingly inconsequential in our daily experience: it’s what allows a pair of people to see the same thing, and yet retain two totally different perspectives of it. To boil it down even further, it’s the sensitivity for nuance.

But what is it that gives us humans these attributes? For one, an inquisitiveness born of our human condition: those uniquely personal upbringings and life stories, our pains and sufferings which have contributed toward the need for answers from life. One of the greatest drivers in humans is our distinctive lack—that is, the things we’ve lost or miss, the things we’ve never had but continue to long for out of some uncanny sense for what could fulfill us, what could fill those aching holes in our being.

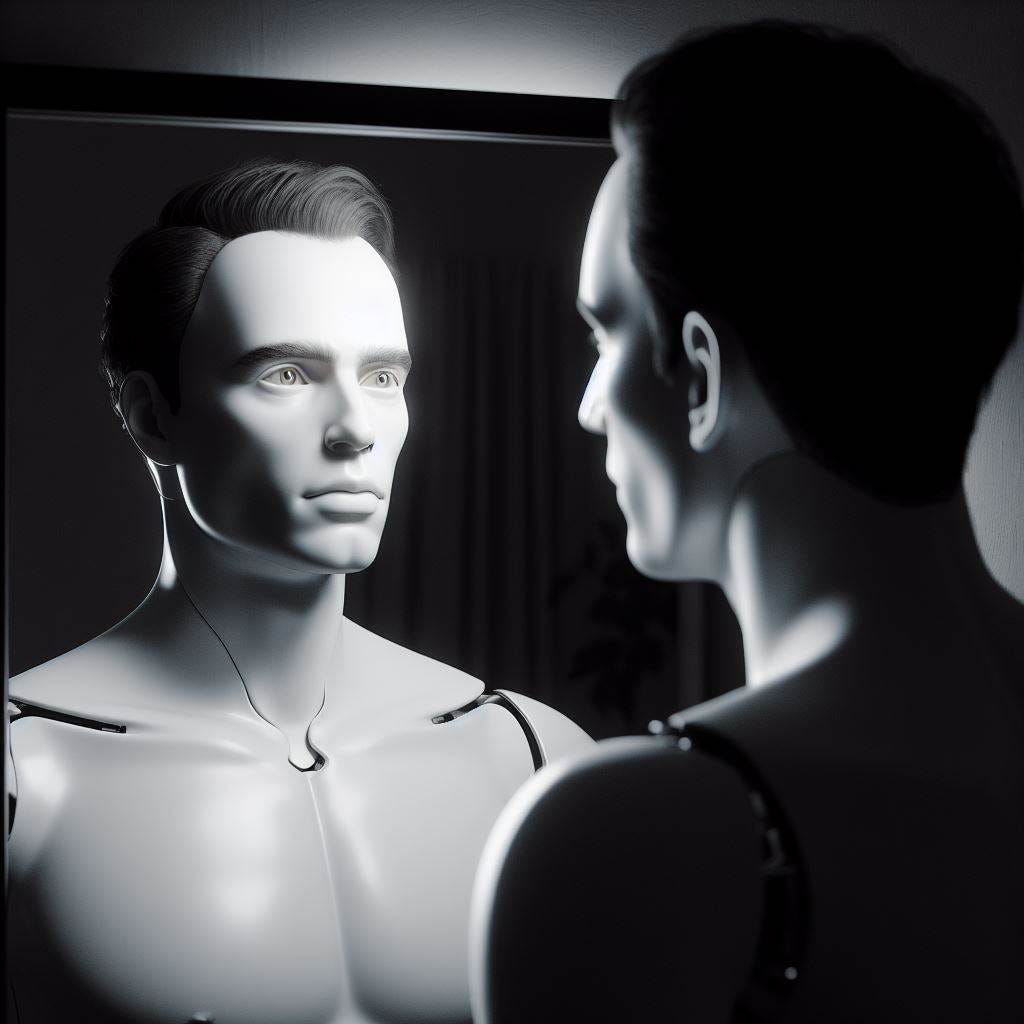

What makes humans unique from AI is that searching wonder, the endless questing for unknowns born of our deep scars and imperfections, the hazy anchors of our nostalgic remembrances. It’s as if to find the answers would validate the wounds we’ve accumulated from the depths of our childhoods, somehow explain—or at the least justify—those teeming early swarms of solitary anguish. In short: what makes us rummage and grope so unremittingly is our need to fill the voids that life has left us with.

When an author plays with words, wracking himself to find that perfect expression or turn of phrase, in many ways he is seeking to break through the psychic confines of banality, of ordinariness, and the status quo of normality. He grasps at the universe in the hopes of scratching through some shroud of obscurity toward the lighted edge of meaning. But ever important is the knowledge that it is the furnace of his unique story, with its many shortfalls and unanswered questions, which drives him so.

In the age of AI replacism we’re left pondering the question of what is our value as humans? Is there anything we offer that is genuinely unique, irreplaceable, and singular enough to warrant our adamantly self-righteous anti-AI nativism?

RB Griggs narrows his sights on this in his brilliant piece:

He writes:

When most people think of Romanticism, they think of poets like Wordsworth and Coleridge pioneering new poetic forms to explore the sublime depths of nature and emotion. Their “lyrical ballads” are seen as part of an artistic crusade, a spiritual and moral response to the grim march of the Industrial Revolution.

He notes that Romanticism was a pushback against much more than just that. After Newton, Descartes, and others, “Reason became exalted above tradition, religion, and history. Knowledge became the ultimate virtue, and the pursuit of universal truths became the driving aspiration. Surely every field could apply Newton’s methods to discover laws with similar power and precision. Reason became the master key that could unlock all the mysteries of the universe.”

So how did the Romantics respond to this assault not on but of Reason?

They rejected all of it.

They didn’t see reason and knowledge as keys to universal truths; they saw reason and knowledge as prisons. Truth didn’t come from reason, it came from beauty, and it was the job of the artist to find it. Art wasn’t about revealing ideal perfections hidden in nature. The point of art was creation—to bring something new into the world, to will your very spirit into existence.

He goes on:

For the Romantics, the only virtues that mattered were freedom and authenticity, and they only felt free when they were aligned with the self-creation of the universe. They didn’t care about structure or logic or ideals.

We too are now seeking ways to cope with the modern fourth industrial revolution. Riggs’ idea is one after my own heart: he calls for a neo-Romantic revolution. He then outlines a whimsically hypothetical future where humankind has splintered into underground resistance sects adopting an indecipherable secret language called Singslang to thwart the inevitable AI training data harvest octopus which seeks to homogenize and sterilize language, and then our ideas.

Now, in 2025, the Neo-Romantic rebellion is fully here. Slang released something in us, challenging our most tightly held beliefs. Maybe the empirical world isn’t the only world worth knowing. Maybe the true isn’t the rational. Maybe there is something sublime in the inexplicable.

We’re starting to find the right balance with our machines. We’re happy to give AI’s logic and calculation. In return, we will reclaim the paradoxes at the heart of the human journey: between reason and emotion, the conscious and subconscious, the animal and the divine.

This is the Neo-Romantic rebellion. We seek the sacred. We tell new stories. We thank the machines for showing us what we lost.

The fanciful idea converges with my own thoughts about the incipient age of AI inadvertently presenting an opportunity for us to do an internal audit of ourselves, to uncover what it is that truly makes us human, that separates us from the pastiche soon to multiply and overrun every facet of society, acting as our surrogate for Big Tech and Big Corps. As RB Griggs notes, the machines present an unexpected opportunity to ‘show us what we lost’.

John Carter, too, referenced this increasingly vexatious dilemma in his new piece, which I likewise recommend:

He writes:

That’s all to say that as AI becomes increasingly nuanced in imitating us down to the micro-expression, we must redouble our search for the pith in ourselves, embrace the rooting quest to discover what distinguishes us—what sacred traits can be worn as keepsakes, inviolably ours alone, forever unassailable by the all-ingesting plankton of AI which seeks to vacuum up our most precious effects, to patch together into a synthetic quilt and wear it as a mask.

I used writing as a metaphor for the wider argument of commensurability between our humanness and AI puppetry. John Carter writes above that, despite getting ever more subtle, AI mimicry can—for the time being—still be picked out with a ‘gut feeling’; an intangible ersatz quality. But what is that ersatz thing? Ask an expert in any competitive field and they’ll tell you the magic always lies in the last 0.1% of creation. Here too, what encapsulates our very human ethos and subjectivity lies in that final ephemeral sliver, which conceals a vast gulf of separation between us and the imitation.

As to the essence of this gulf: clues abound around us.

Several years ago pop science posed a fascinating series of experiments purporting that humans can be made to fall in love with one another by following a simple series of instructions; love on command. It boiled down to sitting still while facing each other, staring deeply into one another’s eyes and answering a series of progressively intimate questions asked in turn.

13. If a crystal ball could tell you the truth about yourself, your life, the future or anything else, what would you want to know?

14. Is there something that you’ve dreamed of doing for a long time? Why haven’t you done it?

17. What is your most treasured memory?

18. What is your most terrible memory?

25. Make three true “we” statements each. For instance, “We are both in this room feeling … “

30. When did you last cry in front of another person? By yourself?

The quote from a participant below encapsulates part of the esoteric process:

“[T]he real crux of the moment was not just that I was really seeing someone, but that I was seeing someone really seeing me. Once I embraced the terror of this realization and gave it time to subside, I arrived somewhere unexpected.”

It’s a heady brew of both an empathic connection as well as sudden vulnerability, a feeling of being undressed in front of a stranger. The questions eventually lead to one feeling a sense of familiarity in the stranger’s life story, the life choices inherent in their answers, which precedes empathy and a feeling of closeness. The vulnerability inherent in your own responses reflected onto your counterpart adds to the heightening intimacy which opens a brief door, like a passage to another world, only for you to take together, hand in hand.

I began by describing how the top percentile of writers distinguish themselves from the dilettantes by an irrepressible need for always finding that one small, unexpected slice of magic, which subverts a standard turn of phrase or cliche into something uniquely personal; a stamp of individuality that asserts one’s singular experience of the world. These are the triggers we empathize with, which urge the kinds of responses in us seen in the 36 question love experiment. Your story is my story; or at the least, I see traces, echoes of it in your experience.

This is ultimately what’s missing in AI functionality, and parallels the most common condemnation of the ‘trans women are women’ conceit. Even if trans women could be made wholly genetically identical to biological women, what remains is that a biological male who chose to become a woman at an advanced age—let’s say late teens or even twenties—forewent the trials and travails of womanhood throughout his early life. Thus, he can never lay claim to being fully ‘woman’ given that the sympathetic lineaments of childhood which sculpt and define a woman will be missing from the palette of his lived experience.

In the same way, AI has not endured a human life, from conception through the turbulence of childhood, to adulthood. When AI imitates us, the experiential essence of the act is embalmed in artificiality, a pastiche, though the verisimilitude may be surprising, even uncanny at times. When humans derive pleasure from the creations of other humans, we do so with the understanding that the ligatures of the work are rooted in a sympathetic experience. What can we possibly feel from a story composed by an AI—which may contain all the superficial affects of emotion, the convincing airs and trappings of human experience—but which we know deep down is written by a thing which had not actually suffered through any of it, and so cannot genuinely commiserate with us.

But what about when the provenance of a work of art resists identification, as is increasingly the case in the age of the deepfake? Recall the funerary scene earlier. As humans, we must strive to inject as much of our authentic heart and voice into our work. Like the Singslang argot of RB Griggs’ inspiring essay, we can distinguish ourselves from the artifice by striving to dig deeper, not settling for the facile satisfactions and ‘passable’ efforts. At least for now—while opportunity yet remains—we should plumb down to the ripened piths of our unique subjectivities, embracing those little intangibles, the ephemeral sparks of human wisdom and inspiration, in all their delightful quirks and eccentricities—those which are capable of incubating only within the full breadth of authentic lived experience, in all its not-so-rosy shades.

RB Griggs concludes his essay as follows:

History shows us that humans respond to most disruptions in very weird and unpredictable ways. AI will challenge some of our most deeply held beliefs about the human condition. It seems natural to expect all sorts of wacky movements that will try to define and re-assert the uniqueness of the human spirit.

Regardless of whether our future is Neo-Romantic or not, I hope it includes more emotions, more paradoxes, and yes, even more irrationalities. In other words, more of the things that machines may augment but can never replicate.

AI will undoubtedly continue getting better and better at mimicking us, but so long as it lacks physical form through which to experience all the whirlwind ups and downs and agonies of flesh, it’s doubtful it can ever transcend its imitative pretenses beyond mere digital Kabuki. The day will come, however, in the distant future, when the AIs could be fitted with biosynth bodies, enhanced by the flesh and blood of hormone exchange and sympathetic nervous response with all its impelling urgencies, changing the equation forever.

But that day remains a way’s away.

For now, let us revel in the pageant of the mad and undefinable. Those kernels of asymmetry, the offbeat tics of doubt and irrationality, fraught with outrageous noise which betrays deeper meaning. The loaded die of possibility in each unexpected turn of revelation. The arcana of lies, the gospel of truth, the sinner’s confession, all in one epiphanic rut. Let us don the foolscap and the king’s robe, the monk’s vestments and the ink-stained scrivener’s quill. Let us be prisms to the unarrested madness to which AI will forever remain a hopeful uninitiated, ever consigned to the penumbra of our limitless impossibilities.

What say you, yea or nay?

If you enjoyed the read, I would greatly appreciate if you subscribed to a monthly/yearly pledge to support my work, so that I may continue providing you with detailed, incisive reports like this one.

Alternatively, you can tip here: Tip Jar

Your quality was greater when your quantity was less. Simple enough.

I really enjoyed this read. Hear Hear as the pompous would say.